A mindfulness practice can look something like this: Stand in the shower and let the water run off your skin. Notice how the water feels. What does the soap smell like? Do you feel warm, relaxed?

A mindfulness practice can look something like this: Stand in the shower and let the water run off your skin. Notice how the water feels. What does the soap smell like? Do you feel warm, relaxed?

Or, sit at your desk and close your eyes. Breathe in and out slowly, and focus only on that action. If your mind starts to wander, acknowledge it and return to the breath. Do this for 5 minutes.

Are you still with me?

Mindfulness, as defined by Linda Oxford, a Rochester Hills-based mental health counselor, is тPaying attention, on purpose, without judgment.т Oxford has incorporated mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) practices for more than a decade, which include different types of meditation, yoga, and lectures.

But mindfulness practices take just that т practice. Multitasking may be a rewarded skill at work and at home, but mindfulness is just the opposite. Itтs about focusing on each moment, and learning to let thoughts about the past or future float away.

Itтs not easy, but more metro Detroiters are trying it; therapists, Buddhist leaders, and yoga teachers all say interest in their mindfulness-based programs has increased over the past few years. But what is mindfulness, exactly?

Ь§

Cultivating Consciousness

Mindfulness is not just meditation т although meditation can be a tool used to achieve mindfulness. Thereтs no mantra, itтs not a religious practice, though it does have Buddhist roots (more on this later), and people can do it almost anywhere.

тMindfulness is a practice in the sense that itтs something that you do. Mindfulness is not a technique. We practice mindfulness, but in its essence, itтs a way of being. Itтs a way of cultivating consciousness,т Oxford says.

In Oxfordтs eight-week MBSR class, she teaches her students how to practice mindfulness by walking, sitting, going on a daylong retreat, and even while driving to work. There are many opportunities to practice mindfulness т what seems more difficult is integrating these practices into a normal, busy, and inevitably hectic day.

Amy Johnson, a therapist for the Juvenile Justice Center in Macomb County and special projects coordinator at Oakland University, works with nursing students to help them cope with the stressors associated with juggling school, a job, and personal life.

She gives two different practice examples to help bring individuals back to the present. She breaks it down into simple moves: sit down and close your eyes, breathe in three seconds, hold for three, breathe out for three. Or, stand and lift up one leg and pull it into your chest and try to balance.

Johnson equates meditation to becoming a long-distance runner. Runners start by running down the block, not by running a marathon.

тAnytime we talk about meditation or being still, every time т and Iтm not saying sometimes, Iтm saying every time т people say, тOh, I canтt. My brain always wanders,т like itтs unique тІ But everybody has that problem. Break it into tiny, manageable pieces,т Johnson says.

Christine Dieck, a Troy-based yoga teacher, echoes this sentiment. When she started practicing meditation, she was convinced that she should be able to meditate if she just put in enough effort.

тI had to relax around [the idea of meditation] and understand that the brain is meant to think, thoughts are going to come тІ but if you donтt follow them and attach to them you can kind of let them go by. I had to stop attaching to the idea of a good or bad meditation, which was very difficult,т Dieck says.

She says because she wasnтt getting the results she expected would immediately come with the practice, she wasnтt sure if meditation was worth it.

тThere were times Iтd get up and think, well that was a waste of time. I thought about (television show) Scandal tonight т the whole time. It was very difficult to give up those ideas of getting something, in that sense, out of it,т Dieck says.

But, after she learned to let go of her ideals and expectations of what a тgoodт meditation was, she began to enjoy the practice.

Ь§

More Than Stress Relief

What should people expect to get out of meditation? Can it, or any mindfulness practice, actually help people become more mindful?

Science suggests that learning to cultivate mindfulness, through MBSR classes and meditation, is worth it. Studies have shown mindfulness practices can change a personтs brain.

A 2011 study found that those who participated in an eight-week MBSR had changesܧin brain regions involved in learning and memory processes, emotion regulation, and perspective taking.

There were also decreases in brain cell volume in the amygdala, which helps process emotions and plays a role in fear and anxiety. Studies have also shown participantsт symptoms of social anxiety were lessened.

But the purpose of mindfulness isnтt solely stress relief. Mindfulness, while not a religious practice, does have Buddhist origins.

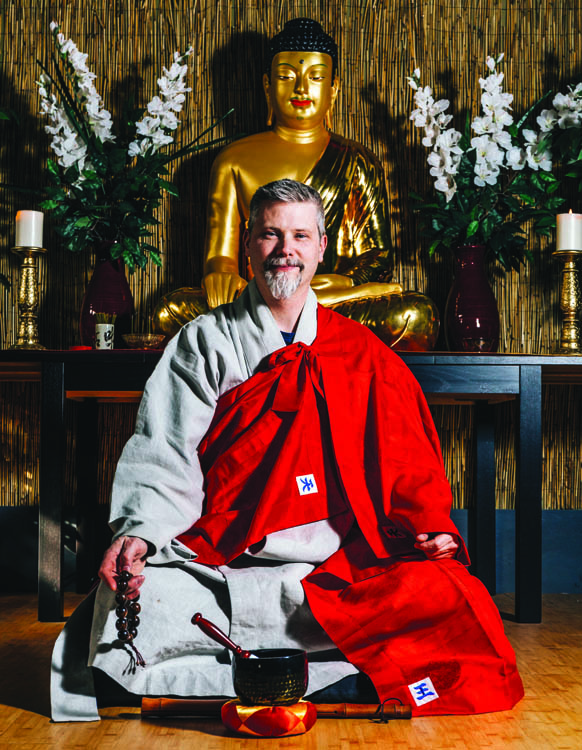

The Dharma Gate Zen Center in Troy offers meditation and services three times a week, Japanese swordsmanship classes, tai chi, and a Buddhist-based recovery program.

Hoden Sunim, the centerтs founder and leader, says the goal of mindfulness practice is to тact from a place of compassion.т

тThe key fallacy to the use of mindfulness is: You can be very mindful and still be really horrible to somebody at the same time,т Sunim says.

He says work extends beyond daily exercises. People have to inhabit the principles of mindfulness in every aspect of their lives. It takes letting go of judgments т of oneself, of meditation, and of others.

т[When youтre practicing mindfulness,] youтre in the minute, you know youтre being a jerk, and youтre still being a jerk, right? Itтs not about mindfulness as much as when youтre being mindful, what are you doing with that mindfulness?т Sunim says.

|

| Ь§ |

|