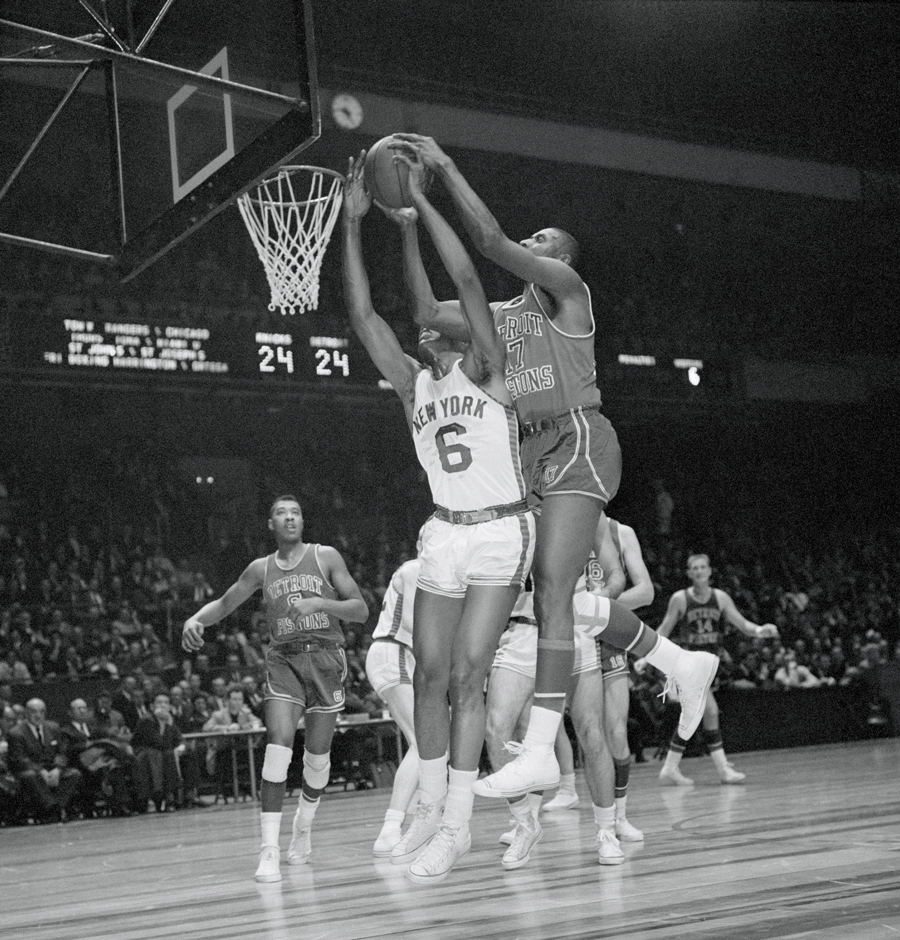

Jumping barriers: Although Earl Lloyd wasnтt exactly a standout player in the NBA, he was the first African-American to play in the league. Here, Lloyd and the New York Knicksт Willie Naulls tussle for ball possession under the basket. // Photograph Courtesy of Getty Images

Jumping barriers: Although Earl Lloyd wasnтt exactly a standout player in the NBA, he was the first African-American to play in the league. Here, Lloyd and the New York Knicksт Willie Naulls tussle for ball possession under the basket. // Photograph Courtesy of Getty Images

On Halloween night in 1950, Earl Lloyd became the first African-American basketball player to step on an NBA court. Lloyd changed the game, giving future stars such as Wilt Chamberlain, Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant, and LeBron James a platform on which to build their basketball careers.

But, as shown in the new documentary The First to Do It, his legacy doesnтt stop there.

He played two seasons т 1958-59 and 1959-60 т with the Detroit Pistons, and finished his NBA playing career with the team. Less than a decade later, in 1968, Lloyd crossed racial divides again when he became the NBAтs first African-American assistant coach for the Detroit team.

Then, in 1971, Lloyd was named the leagueтs second African-American head coach and the first African-American bench coach, also for the Pistons. He coached the first nine games of the 1972-73 season, and the city became his stomping ground.

тHe brought a lot to Detroit,т says Chike Ozah, who co-directed the film with Clarence тCoodieт Simmons Jr. The documentary, which chronicles Lloydтs largely overlooked historical impact, pays tribute to the athleteтs illustrious contribution to the civil rights movement as well as his professional basketball and post-basketball career.

The documentaryтs scenes jump from Lloydтs past to his present, reviewing his accomplishments, which along with basketball included a job as a placement administrator for Detroit Public Schools and an executive position with Chrysler, and juxtaposing them with moments surrounding his death on Feb. 26, 2015. тHeтs an icon and a trailblazer,т Ozah says. тWe wanted to film him in the way he would be OK with.т

Looking back at тThe Big Catт т a nickname given to Lloyd while he was in college at West Virginia State University т the film portrays him as a silent hero, showing old black and white photos of him jumping for rebounds against all-white teams. Ozah and Simmons also interview his teammates from high school and college, who remember Lloyd fondly. Their personal stories paint Lloyd as a gentleman, a scholar, and a damn good athlete.

Before 1950, the thought of basketball as a career for African-Americans was nonexistent. Today, the names and faces seen on TV make enough money to fill swimming pools. Today, Lloydтs name remains somewhat unknown compared to other athletes. However, despite pioneering for todayтs all-stars, the film directors say he enjoyed the anonymity.

тEarl Lloyd was a very humble guy,т Ozah says. тHe wasnтt like, тHey, look at me!т т

In one scene of the documentary, Lloydтs son rummages through plaques, trophies, medals, and insignias that his father kept stored away in a closet. The mementos are out of sight despite their significance to Lloydтs career.

The film shows that he didnтt consider himself a great pioneer in the integration of sports either, especially not of similar significance to Jackie Robinsonтs role in integrating professional baseball. In a famous quote from Lloyd, he says, тIn 1950, basketball was like a babe in the woods. It didnтt enjoy the notoriety that baseball enjoyed.т

тBaseball was sort of this national pastime,т Simmons says. тThere wasnтt much excitement over the black players in basketball, because they were just following their roles, getting boards, being the muscle, so it wasnтt the most glamorous. Had he [Lloyd] been averaging 25 points a game, which I think he could have done, then the conversation changes.т Lloyd was not a standout player in the NBA; he averaged 8.4 points and 6.4 rebounds in 560 games in his professional basketball career.

However, Lloydтs efforts proved to be a culture shock within inner-city communities as he used the sport to encourage kids to cross boundaries. тThe sport not only gets kids out of the hood т everybody has dreams of going to the NBA and thatтs great т but it gives kids scholarships to go to college,т Ozah says.

Detroit flourished into a vibrant basketball community. Championships were won, the fan base grew, but Lloyd, the pioneer, remained a silent hero.

Although not having gained the recognition he deserves in the public eye, Lloyd enjoyed a successful career on and off the court. He was respected in Detroit. In the heat of his career, after being drafted by the Pistons in 1958, Lloyd тfelt like a butterfly emerging from a cocoon,т he said in a 2004 Detroit Free Press interview. He was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2003.

тWe want more people to тІ see the film and make Earl Lloyd a household name,т Ozah says.

тEarlтs legacy can lead to long-term growth, especially in Detroit.т

To learn more about the Earl Lloyd documentary, visit .

|

| Ь§ |

|